18 September 2020

The Internet, editorial responsibility and press cartoons

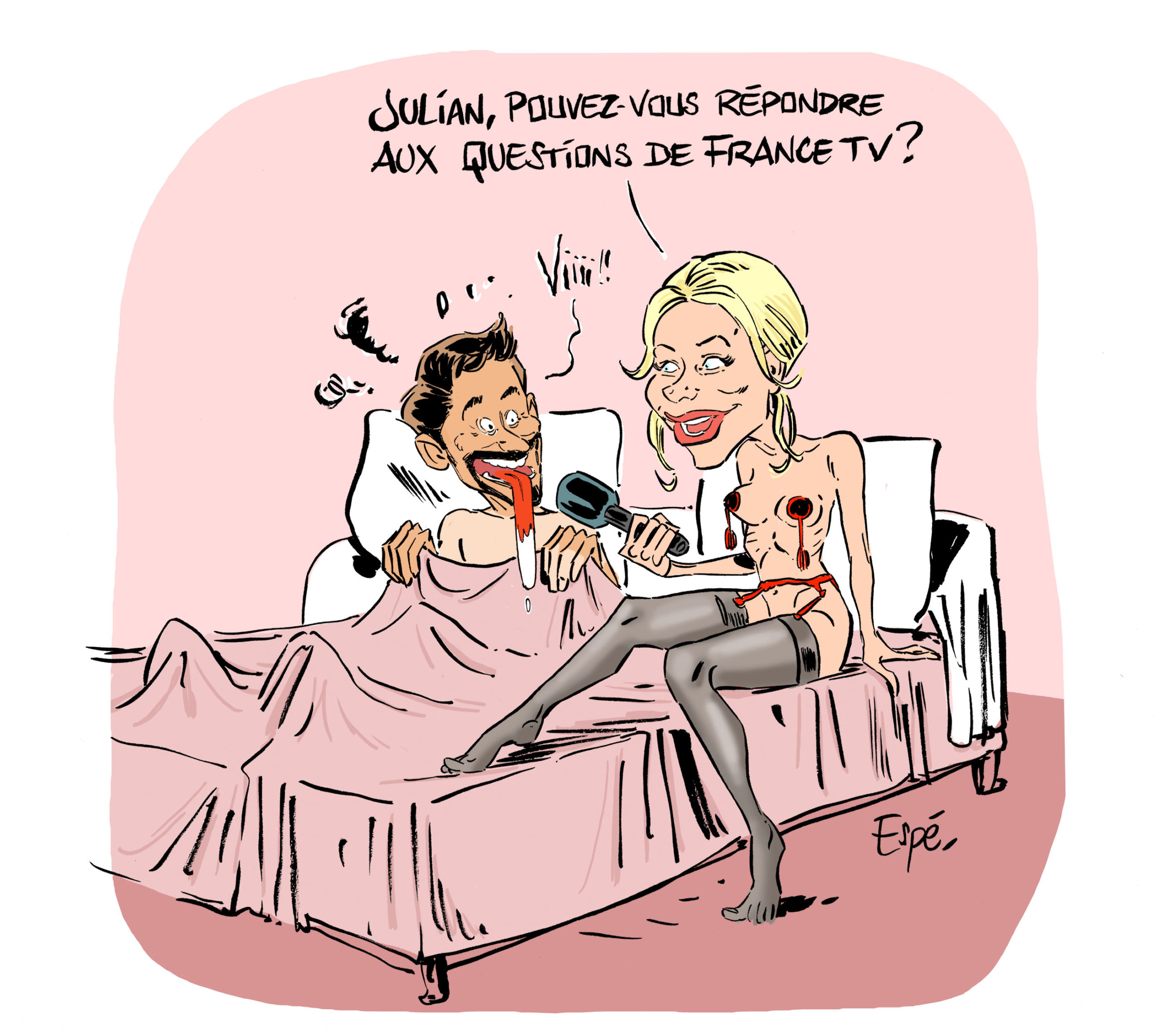

On 6 September 2020, the publication of a cartoon by the cartoonist Espé by the newspaper l’Humanité on its website sparked controversy on social media and led to the termination of the collaboration between the newspaper and the cartoonist.

Cartooning for Peace deplores the violence of some of the reactions on social networks and the threats made against the cartoonist after the newspaper distanced itself from him.

The context

Better known for his comic strips, Espé worked as a volunteer for l’Humanité on the Tour de France, and had drawn cartoons on previous stages of the Tour.

The cartoon in question depicts France Television presenter Marion Rousse sitting on a bed in lingerie, interviewing her partner, rider Julian Alaphilippe. Alaphilippe sticks out his tongue in a manner reminiscent of the wolf in Tex Avery cartoons, as the cartoonist explains. For him, the outfit and pose of the columnist are reminiscent of a series of photographs taken from the Cyclepassion 2012 calendar. The cartoon accompanied a text by columnist Antoine Vayer on the sex lives of sportsmen and women during competitions, which it was intended to illustrate.

The reactions

Immediately criticised by Elisa Madiot, press officer for the Groupama-FDJ team, who described the cartoon as “sexist, degrading and vulgar”, and echoed by Marion Rousse, herself “disillusioned”, the cartoon was widely commented on and shared. Interviewed on RMC Sport, the rider also expressed his displeasure.

In response to the outrage caused by the publication of the cartoon, the newspaper un-published it a few hours after publication. In a Tweet relayed by the newspaper’s account, Sébastien Crépel, co-editor, referred to a “lack of vigilance” and demanded an apology from Marion Rousse. The following day, the editorial team published a letter to its readers in which the co-director in turn described the cartoon previously approved and published by his teams as “degrading and sexist” and announced the decision to cease working with the cartoonist and columnist, while acknowledging a failure of verification.

The cartoonist, for his part, immediately apologised for a cartoon whose intention he felt had been misunderstood: “I’m really sorry, sorry, sorry. The newspaper has apologised, the cartoon has been unpublished and I am no longer working for L’Humanité. I didn’t mean any harm, it was just a caricature. I wanted to evoke the porosity between the media and sport and I wanted to take inspiration from Tex Avery’s cartoons. But I got it wrong. When a cartoon isn’t understood, it’s a mistake, but I never thought it would take on such proportions”.

Despite these explanations and apologies, for several days the cartoonist was inundated with articles, often accusatory, and was the victim of a storm of aggressive comments containing insults and even physical threats, which greatly affected him.

Another example of censorship by popular court

Freedom of expression allows us to make fun of anyone, regardless of their origin, sex, beliefs or notoriety, particularly through cartoons. Within the bounds of the law and even if it means causing a nuisance, whether intentionally or not. An artist may not find an audience, and his or her work can never be summed up in a single work.

Freedom of expression also allows each and every one of us to like or dislike a cartoon and to make that known. But this must be done in a debate that does not include insults, threats or harassment.

Furthermore, a year after the New York Times (international edition) sacked its cartoonists because of an online controversy, Cartooning for Peace is concerned to see a new editorial team dissociate itself from a cartoonist following an online controversy sparked by a cartoon it had published with full knowledge of the facts. This is a phenomenon that has become commonplace and has unfortunately taken its toll on many cartoonists around the world. Instead of engaging in a healthy debate, a contributor is immediately sacrificed on the altar of propriety.

Today, more than ever, it is essential to remember that only the courts can decide whether a cartoon is reprehensible and, for the rest, to call for dialogue between the people concerned and for the moderation of debates.